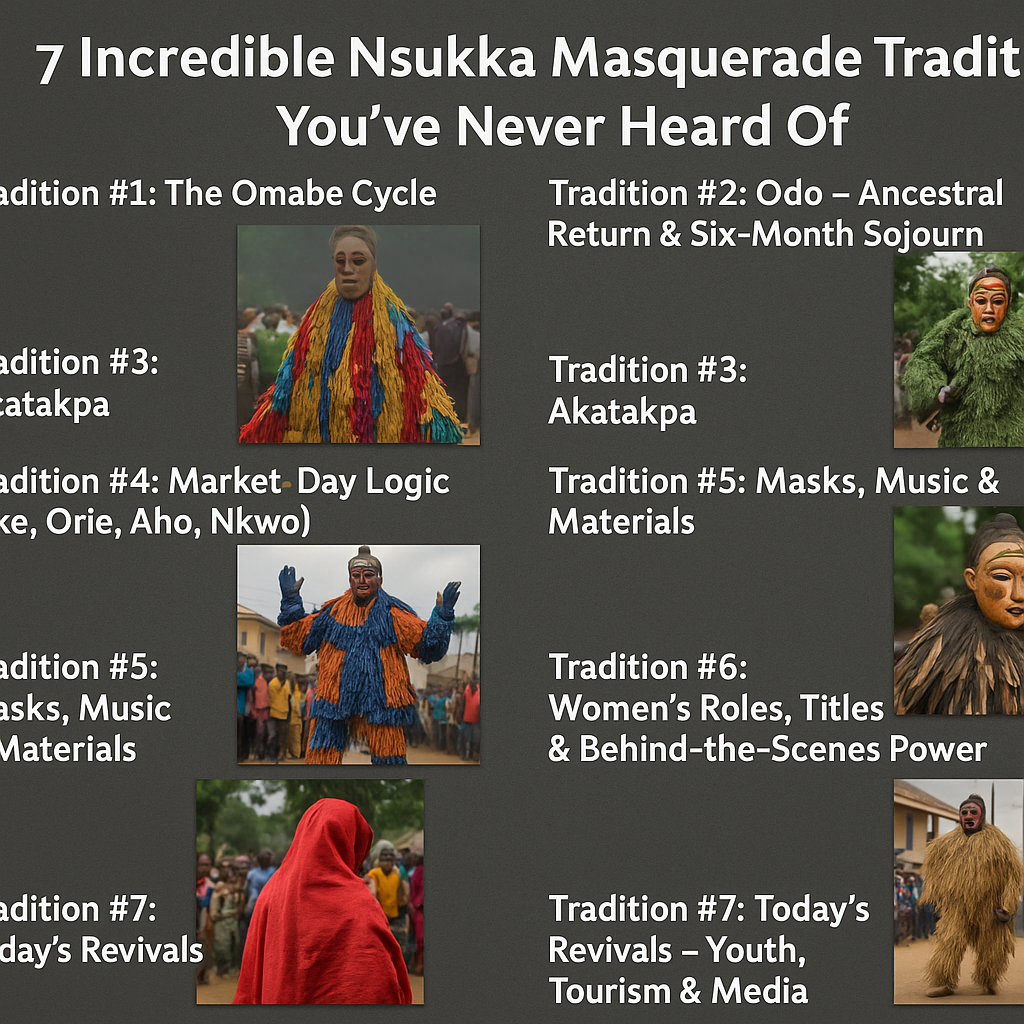

7 Incredible Nsukka Masquerade Traditions You’ve Never Heard Of

Quick Overview & Why This Matters

Curious about the living heartbeat of Igbo culture in the Nsukka zone? This guide unpacks the sacred, playful, and often misunderstood world of masquerades—with clear, credible notes you can use for school projects, research, or travel planning. You’ll meet Omabe, Odo, and Akatakpa, learn how market days shape schedules, and see how elders and youth keep things alive today. Most important, you’ll see why Nsukka masquerade traditions carry meaning that goes far beyond entertainment. We also include a comparison table and FAQs toward the end, so you can revise fast before presentations or exams.

(Scholars describe detailed Omabe festival phases—pre‑arrival, arrival, events, departure, and post‑departure—showing how structured and purposeful the cycle is.)

What Makes Nsukka masquerade traditions Different?

First, the Nsukka area (in today’s Enugu State) hosts a dense cluster of masking practices that are ancient, artful, and socially active. You don’t just “watch” them—you experience them. Some acts are healing or protective; others are disciplinary or theatrical. Across communities, names, calendars, and tonality vary, yet the core idea remains: masquerades are spirit‑powered institutions that help steer communal life. (You’ll see Omabe, Odo, Akatakpa, Oriokpa, and others mentioned in academic and regional studies.)

A note on sources: Different researchers record nuances differently. Some analyses treat Omabe and Odo as distinct in tone or calendar; others argue they’re closely linked or even used interchangeably in some Nsukka contexts. We’ll show both views where they appear in credible work.

How to Use This Guide (For Students & Researchers)

- Expect variation: Every town may “do it a bit differently.”

- Ask before recording: Always seek local consent for photos or notes.

- Observe roles and taboos: Some spaces and rites aren’t for everyone.

- Talk to multiple people: Elders, youth, and titled men/women may have different emphases.

- Cross‑check dates: Festival cycles can shift after long breaks or revivals.

Tradition #1: The Omabe Cycle — From Pre‑Arrival to Post‑Departure

Why it stands out: Omabe is one of the best‑documented cycles in the Nsukka zone, with a clear set of stages and a reputation for both spectacle and social messaging. Studies and cultural briefs frequently note that in several Nsukka communities the Omabe festival operates on a multi‑year interval, commonly cited as every five years—though local calendars can vary.

Pre‑Arrival Rites & Community Preparation

Weeks to months ahead, communities clean pathways, repair shrines, and tune instruments. Elders set guidelines; youth rehearse drumming and movement. Researchers outline this as a distinct “pre‑arrival” phase, useful for students who want to map ritual flow charts.

Performances: Music, Masks & Moral Messaging

On festival days, you’ll hear ogene gongs, igba drums, and the piercing oja flute. Masks range from austere to flamboyant, and performances can flip from solemn to satirical. Depending on the town, Omabe acts as a guardian spirit, a moral teacher, or a community purifier—readings differ, but many sources stress its role in order and cleansing.

Some write‑ups frame Omabe as distinct from Odo (with Odo emphasizing ancestor‑return), while other scholarship treats them as closely related categories in Nsukka thought. Keep both interpretations in mind when you analyze field notes.

Departure, Aftercare & Taboos

After the peak days, there’s a “cool‑down” period—taboos relax, markets steady, and households tidy up. Documenting these “aftercare” moments helps researchers see how festivals regulate community rhythms beyond the spectacle itself.

(Within this section, remember that calendars and emphases differ by community—even within the Nsukka zone.)

Tradition #2: Odo — Ancestral Return & Six‑Month Sojourn

Why it stands out: Odo centers the idea that ancestors visit the living on a scheduled rhythm. In several Enugu‑area communities, including those culturally close to Nsukka, scholars document a biennial cycle in which the Odo spirits return and dwell among the living for about six months before a formal send‑off. Community specifics vary, but this pattern shows up consistently in research.

The Calendar Rhythm

You’ll hear people say, “Odo is coming,” followed by months where the social atmosphere feels different—certain behaviors tighten or relax, and some paths or groves are off‑limits.

Social Control: “Courts,” Fines & Mediation

Academic studies remark that, in the Nsukka area, Odo has historically carried legislative and judicial weight—mediating conflicts, enforcing fines, or calling out wrongdoing. This helps explain the deep respect (and fear) it commands.

Farewell & Reintegration

Odo’s departure closes a chapter: fines are settled, disputes cooled, and families return to everyday rhythms. Students should track how households mark this transition—it’s rich material for essays on the social functions of ritual.

Tradition #3: Akatakpa — Satire, Sting & Street‑Level Sanctions

Why it stands out: If Omabe leans sacred and Odo leans ancestral/legal, Akatakpa leans satirical and corrective. It’s widely associated with Nsukka and surrounding communities, using humor, mock trials, and quick “stings” (sometimes literal canings) to police behavior in public view. Academic and regional journals list Akatakpa among the area’s prominent masquerades.

What to watch for:

- Satire with a message: Performers lampoon gossipers, thieves, or lazy folks.

- Crowd dynamics: Laughter and nervous energy coexist; the line between joke and warning is thin.

- Civic effect: People adjust behavior—fast.

Tradition #4: Market‑Day Logic (Eke, Orie, Aho, Nkwo) & Gendered Balance

A compelling thread in Nsukka scholarship links masquerade timing to the four‑day market week—Eke, Orie, Aho, and Nkwo. One line of research frames Omabe as masculine, often aligning with Eke/Orie timings, and Odo as feminine, leaning toward Aho/Nkwo. Not all towns follow this neatly, but the pairing shows up in Nsukka‑focused writing and is a useful lens when you compare field notes.

Why it matters:

- It reveals an internal logic to scheduling.

- It encodes gendered ideas of balance and alternation.

- It’s a reminder that “calendar” in Igbo thought is moral, not just temporal.

Tradition #5: Masks, Music & Materials

Masks & meaning: Woodcarving in the zone ranges from smooth, geometric planes to heavily textured faces. Some masks exude quiet dread; others are elegant or comedic. Costume layers can include cloth wrappers, raffia, animal skins, and beadwork—each cueing rank or role.

Music: The soundscape mixes ogene (iron gong), igba (drum), and oja (flute). The tempo can switch from stately to explosive as a signal: stand back, make way, or join in song.

Why researchers care: Tracking the aesthetic code—how masks, rhythms, and movement align—helps you read what a performance is “saying” even if you don’t understand every line of the lyrics.

(Scholars tie visual language in Nsukka masking to wider aesthetic ideas, including duality and balance reflected in Omabe–Odo pairings.)

Tradition #6: Women’s Roles, Titles & Behind‑the‑Scenes Power

You’ll often hear that “women don’t enter the grove,” which is usually true for specific restricted spaces. But that’s not the whole story. In Nsukka communities, women play vital roles—from financing to tailoring to knowledge transmission.

- Oyima (friend of the spirit) & Oyi Odo titles: Scholarship notes named titles that mark high‑status women with exceptional access or recognition in masking systems—especially at old age.

- Costume economy: Among Nsukka Igbo, women sell accessories and weave/sew masquerade costumes, supplying wrappers and other essentials that literally clothe the spirits.

This behind‑the‑scenes power shapes what you see on performance day. It also means interviews with market women and seamstresses can be gold for student projects.

Tradition #7: Today’s Revivals — Youth, Tourism & Media

After periods of dormancy, many towns have revived festival cycles, with youth participation surging. Recent studies in Nsukka‑Igbo communities link these revivals to local tourism and creative industries—think music, fashion, and media. Revivals can also restore pride and rebuild the social functions that masquerades historically served.

What to watch:

- Training the next generation (drumming, carving, etiquette).

- Scheduled “come‑backs” after years of pause.

- Rules made explicit (for safety in larger crowds).

Comparison Table: Omabe vs Odo vs Akatakpa

Remember: specifics vary by town. Treat this as a field guide, not a rigid map.

| Feature | Omabe | Odo | Akatakpa |

|---|---|---|---|

| Core Idea | Guardian/ordering spirit; purification & performance | Ancestors “return” to live with the people temporarily | Satirical, corrective, public discipline |

| Typical Rhythm | Multi‑year cycle; often cited as ~5 years (varies) | Frequently biennial with ~6‑month presence (varies) | Often seasonal/periodic; tied to public order events |

| Atmosphere | Sacred + spectacular | Solemn, juridical, communal | Humorous but fear‑tinged; quick sanctions |

| Social Function | Moral teaching, cleansing, cohesion | Mediation, fines, community rules | Calling out misconduct; behavior change |

| Scheduling Logic | Linked in some analyses to Eke/Orie | Linked in some analyses to Aho/Nkwo | Public‑facing; less tied to sacred calendar |

| Who to Interview | Elders, drummers, carvers | Custodians, elders, dispute mediators | Youth teams, market traders, security helpers |

Sources supporting specific rows include research on Omabe cycles and Odo’s judicial roles, plus Nsukka‑area masquerade lists.

Fieldwork Tips for Students (Ethics & Safety)

- Ask first. Never assume you may record, post, or approach.

- Mind red zones. Groves, shrines, or masked routes can be restricted.

- Dress modestly. Blend in and avoid bright, attention‑grabbing outfits.

- Stay with a local guide. They’ll read cues you might miss.

- Verify dates. Festival calendars can shift after revivals or local events.

- Balance your sources. Speak to elders, titleholders, women traders, and youth performers.

FAQs

1) Are women allowed in Nsukka masquerade traditions?

Women often don’t enter restricted groves or handle certain paraphernalia, but research documents vital roles: funding, sewing, selling accessories, and, in some cases, respected titles like Oyima or Oyi Odo at advanced age. Always follow local guidance.

2) How often do Omabe festivals occur?

A common pattern reported for Nsukka‑area communities is every five years, but towns may vary. Check locally before you travel or plan research.

3) Does Odo really “live” with people for months?

That’s a well‑documented idea: in parts of Enugu State culturally close to Nsukka, Odo’s biennial arrival includes a months‑long stay followed by a formal send‑off. Local calendars differ.

4) What does Akatakpa actually do?

Akatakpa is the sharp, satirical edge of masking—mock trials, public warnings, and sometimes quick canings that push people to behave. It’s listed among key masquerades shown in Nsukka‑area studies.

5) Are Omabe and Odo the same thing?

Depends on who you ask. Some accounts treat them as distinct (e.g., ancestor‑return emphasis for Odo) while other scholarship in Nsukka contexts treats the terms as closely linked or even interchangeable. Cite both views in essays.

6) Why are market days (Eke, Orie, Aho, Nkwo) important?

They structure timing and meaning. One Nsukka‑focused reading pairs Omabe with Eke/Orie (masculine) and Odo with Aho/Nkwo (feminine). It’s a helpful lens, though not a rigid rule.

7) Can I attend if I’m not from the community?

Often yes, but go with a local host, respect boundaries, and don’t cross security lines. When in doubt, ask.

8) What’s the single best research tip?

Document the before and after, not just the performance days—many social effects happen in those quieter phases.

Conclusion

You’ve just explored seven pillars that keep the heart of Nsukka masquerade traditions beating: Omabe’s structured cycle, Odo’s ancestral law‑and‑order, Akatakpa’s satirical sting, the four‑day market logic, the craft of masks and music, women’s powerful roles, and the modern revivals drawing youth back in. If you’re a student or researcher, use the comparison table to frame essays, and mirror your field notes against multiple sources so you present a fair picture.

Enjoyed this deep dive? Check out more posts on my website—there’s plenty more on Igbo culture, performance, and community life waiting for you.

you may also like : Fort Boyard Prison: Surprising Facts, Rich History & Easy Travel Tips (Ultimate Guide)